- March 24, 2022

- Don Burton

- Intellectual Property

Last month, in Qualcomm, Inc. v. Apple Inc., No. 2020-1558, 2029-1559, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 2836 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 1, 2022), the Federal Circuit enforced the literal language of the relevant statute and held that a petition for inter partes review (IPR) cannot challenge the validity of a patent on the basis of "applicant admitted prior art." The ruling is significant because it could create practical difficulties for persons trying to invalidate a patent through the IPR process, and sets forth a test that could require further clarification from the court, as explained below.

IPR is an administrative procedure that was included in the America Invents Act of 2011 to address criticisms that the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office ("PTO") in recent decades has issued too many dubious patents. Under the IPR process, anyone other than the patent owner is allowed to petition the Patent and Trademark Appeal Board ("PTAB") of the PTO to cancel an issued patent. The petition may challenge validity of the patent either on the basis that a single piece of prior art (prior technology in the relevant field) describes the invention claimed in the patent, invalidating the patent under 35 U.S.C. § 102, or on the basis that the prior art as a whole renders the claimed invention "obvious," invalidating the patent under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

Importantly, the categories of "prior art" that can be relied on in a petition for IPR are narrower than in civil litigation. "Congress sought to create a streamlined administrative proceeding that avoided some of the more challenging types of prior art . . . such as commercial sales and public uses, by restricting the 'prior art' which may form a basis of a ground [of invalidity] to prior art documents." Qualcomm, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 2836 at *16 (emphasis added). Thus, the challenge under Sec. 102 or 103 can be based "only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications." 35 U.S.C. § 311(b).

The issue in Qualcomm was whether "applicant admitted prior art" fell within the scope of "patents or printed publications." (Qualcomm, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 2836 at *2). "Applicant admitted prior art," or "AAPA," is technology that the applicant concedes in the patent application itself is part of the prior art. AAPA happens because of a common approach to explaining what is novel about the invention in the patent application's "background of invention" section (which is then included in the issued patent), which is to contrast the invention with the prior art, and then to state how the invention overcomes a problem that was unsolved by the prior art. An application for a new type of electric can opener, for example, might first concede that conventional electric can openers have been around for decades, then explain how the invention has a feature that overcomes a problem with those conventional can openers.

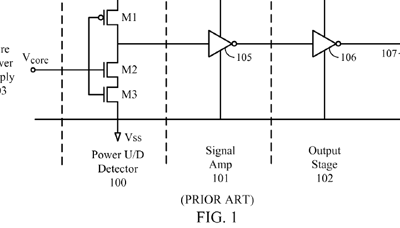

The claimed invention in Qualcomm involved technology perhaps more intricate than electric can openers, but otherwise the applicant used the same approach as in my example. The patent at issue in Qualcomm ("the '674 patent") relates to "integrated circuit devices with power detection circuits for systems with multiple supply voltages." 2022 U.S. App LEXIS 2836 at *2. The background of invention section of the '674 patent includes Figure 1, which "depicts a 'prior art' 'standard POC [power on/off-control] system with a power-up/down detector.'" Id. at *3. Thus, Figure 1 is applicant admitted prior art. The patent goes on to "assert[ ]that there are problems with the prior art solution in Figure 1 . . . . [and] [t]he '674 patent avoids these problems by adding a feedback network to increase detection speed." Id. at *3-4.

Apple argued that the '674 patent was obvious in light of i) the admitted prior art, Figure 1, in combination with ii) a published patent application (the "Majcherczak" reference). Id. at *6. Apple contended that Figure 1 was fair game as a basis for an IPR, since it is contained in a patent, i.e., a printed document. The Federal Circuit, though, held that the AAPA in the '674 patent is not itself prior art but rather a description of prior art. The statute (sec. 311(b)) requires the patents or printed publications to be, according to the court, "themselves . . . prior art to the challenged patent." Id. at *10. The AAPA cited by Apple was "not contained in a document that is a prior art patent or prior art printed publication." Id. at *13-14 (emphasis added).

The Court distinguished its earlier decision in Koninklijke Phillips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2020), in which it was held that in an IPR the PTAB can consider prior art "general knowledge" in determining whether a claimed invention is obvious. Id. at 1338. Part of the obviousness inquiry is whether "the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious . . . to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains." 35 U.S.C. § 103. That determination, i.e., whether the invention would have been obvious to "a skilled artisan," Koninklijke, 998 F.3d at 1337, "necessarily depends on such artisan's knowledge." Id. (citation omitted). In Koninklijke, the claimed invention was obvious based on a printed publication when viewed "in light of the general knowledge of a skilled artisan" about "pipelining," which the petition contended was "a well-known design technique" in the multi-media field. Id. at 1333, 1334, 1338.

Following Koninklijke, it would be proper to use AAPA as "a factual foundation as to what a skilled artisan would have known at the time of invention." Qualcomm, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 2836 at *15-16 (citation omitted). There is nevertheless a difference, the court explained, between basing a challenge "solely" (id. at *18) on applicant admitted prior art and such art being used merely "the background knowledge possessed by a person of ordinary skill in the art" for purposes of determining obviousness. Id. at *16.

What is the effect of Qualcomm? Certainly, after Qualcomm, no petitioner for an IPR will be foolish enough to say that it is challenging a patent on the basis of AAPA. Petitioners will instead claim that their basis for obviousness is a prior art patent or publication viewed in light of the knowledge of a skilled artisan, which knowledge is shown by the AAPA. Will that, however, always avoid the issue raised in Qualcomm? In Qualcomm, the court could not say on which side of the basis/ general knowledge line Apple's argument fell, and remanded that determination to the PTAB. 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 2836 at *18. Thus, Qualcomm could lead to fights over whether a petitioner who claims it is citing AAPA merely for general knowledge is actually citing it as a "basis" for invalidity.

Petitioners would be well advised to avoid a dispute over whether AAPA is being used as a "basis" versus being used as "general knowledge" by digging up another document that describes the AAPA. However, easier said than dug -- such publications can be frustratingly elusive. Probably every associate in a law firm has had the experience of searching for a case to cite in support of a point of law so fundamental, so incontrovertible, so commonsensical . . . that no court seems to have ever stated it. Tracking down written descriptions of what is obvious to a skilled artisan in a field of technology can be just as difficult.

As a result, by necessity, petitioners are likely to continue to refer to AAPA during IPR proceedings, which could require the Federal Circuit to define criteria for determining the difference between "basing" an IPR petition on AAPA and merely citing AAPA for general knowledge. It will also be interesting to see if the Federal Circuit will ever revisit its very literal approach to the statutory term "prior art patents and publications." Conversely, one wonders whether the court will examine whether there should be limits on the doctrine expressed in Koninklijke that in an IPR the petitioner can use unpublished, unwritten knowledge of the "skilled artisan" as part of a Section 103 obviousness argument, the usage of which is in tension with the statute's goal of a streamlined proceeding, where the validity argument is based solely on publications. Setting aside speculations about future developments, though, the lesson for the practitioner from Qualcomm is that, despite the difficulties, the safest course for IPR petitioners and their experts is to exhaustively search for prior art publications that can be used in lieu of applicant admitted prior art.