- August 3, 2020

- Melinda Burton

- business litigation

As those of you who have seen the movie “Legally Blonde” may remember, when Reese Witherspoon’s character Elle Woods takes over as lead defense counsel during the trial, she enters the courtroom not wearing the dark suits that she had worn previously but a bold, pink sparkly dress that reflects perfectly her personality and style. Ms. Witherspoon and her company Draper James no doubt had sincere and good intentions when it offered to provide teachers with a free dress as a token of gratitude during the COVID-19 pandemic. But as the saying goes, “no good deed goes unpunished” and that appears to be what is happening now with Draper James and Reese Witherspoon being sued in a nationwide class action for what the plaintiffs are calling a “scam” or an unlawful lottery sweepstakes. While the rules of haircare may be simple and finite, the laws regarding marketing promotions and giveaways, maybe not so much.

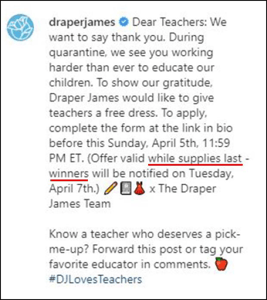

On April 21, 2020, the plaintiffs filed their first complaint in California state court alleging that, “on or about Thursday, April 2, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. Witherspoon’s fashion label Draper James announced the following offer on its Instagram page”:

“Dear Teachers: We want to say thank you. During quarantine, we see you working harder than ever to educate our children. To show our gratitude, Draper James would like to give teachers a free dress.” (Complaint, ¶ 26).

The form that teachers had to complete was a Google Docs form that required the teachers to provide their contact information and “education employee identification information, including pictures of their school IDs, the grade level and subjects they teach as well as their school name and state.” (Plaintiffs allege that this information has “independent value, with initial estimates as low as 50 cents to $5 per name in a commercial database” for marketing purposes and “is also of value to hackers and cyber criminals.”). (Complaint, ¶¶ 27-29).

Draper James’ supply of dresses to give away was 250 dresses. It figured that many more than that number of teachers that would apply, but it still, perhaps naively, underestimated the lure of something free. Draper James’ representatives “had expected less than 10,000 applicants” but “close to a million [teachers] … filled out the Google Docs applications.” (Complaint, ¶¶ 37-38).

In the complaint filed in April, the plaintiffs further alleged that “Ms. Witherspoon specifically endorsed and promoted this offer. In a press statement on or about April 2, 2020 that was repeated on both The Today Show and Good Morning America, Ms. Witherspoon stated: ‘These past few weeks have shown me so much about humanity. I’m an eternal optimist, so I always look for the bright side of things. And I have been so encouraged by the ways people are really showing up for each other. Particularly the teachers.’ ‘During quarantine, teachers are broadcasting lessons from their own homes and figuring out new remote-learning technology and platforms on the fly, all while continuing to educate and connect with our kids,’ she said. ‘Advocating for the children of the world is no easy task, so I wanted to show teachers a little extra love right now.'” (Complaint, ¶ 30 (emphasis omitted)).

In addition, “[o]n or about April 3, 2020, both The Today Show and Good Morning America promoted this offer, exclaiming ‘Reese Witherspoon’s clothing brand is giving away free dresses to teachers’ or ‘Reese Witherspoon’s label Draper James is giving free dresses to teachers’ or ‘the Oscar-winning actress wants to show her gratitude during the coronavirus pandemic’….” (Complaint, ¶ 32). In addition, according to the complaint, “Ms. Witherspoon was publicly feted for making this offer. The Today Show’s website stated ‘Witherspoon’s sweet gesture is just the latest from fashion and beauty companies that are stepping up to show their appreciation to essential workers during the pandemic. Medical workers are being offered everything from free shoes to wedding dresses.’ Good Morning America’s website stated: ‘Reese Witherspoon’s clothing brand Draper James is giving back to teachers to show that their efforts to help students during the coronavirus pandemic are not unnoticed.’ Her efforts were promoted next to those of Oprah Winfrey, who had donated $10 million for COVID-19 relief, and other celebrities of Ms. Witherspoon’s stature who made donations in the millions of dollars each.” (Complaint, ¶ 33).

The plaintiffs also alleged that “there was no limitation on quantity on this offer other than the vague illusory comment ‘(Offer valid while supplies last – winners will be notified on April 7th.)’. There was no indication this was some form of lottery, or that Defendants would be making an unreasonably limited number of products available under this offer….Nothing in the initial FAQ disseminated by Defendants disclosed a limitation (sic) this offer was limited to 250 people….” (Complaint, ¶ 31). And “[w]hat is worse,…within days of announcing the offer and receiving [the plaintiffs’ personal information], Defendants began bombarding Plaintiffs and class members with promotions and discount offers…. [W]hen consumers began expressing outrage at being deceived, all Defendants did was offer consumers a 30% discount on Draper James products – a rebate that would result in Defendants making money off of its now rejected offer….” (Complaint, ¶ 41).

The plaintiffs alleged that the promotion and offers were “false and misleading” (Complaint, ¶ 45) and they brought five claims against Ms. Witherspoon and Draper James: (1) breach of contract, (2) promissory estoppel, (3) restitution, money had and received, unjust enrichment, quasi-contract and assumpsit, (4) violation of the California Consumers Legal Remedies Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 1175, et. seq., and (5) violation of the California Business & Professions Code § 17200, et. seq. They sought damages, restitution, injunctive relief and payments of attorneys’ fees and costs.

In response, on June 4, 2020, Draper James removed the lawsuit from California state court to the United States District Court for the Central District of California, and thereafter on July 10, 2020, Reese Witherspoon and Draper James filed a Motion to Dismiss (“MTD”). They described the plaintiffs’ lawsuit as an “unjust attempt to exploit Draper James’ good intentions to honor the teacher community by gifting hundreds of free dresses.” (MTD, p. 9). They argued that there was no deception and no harm because the Instagram post which plaintiffs claim constituted a contract “made clear that entrants had an opportunity to receive a free dress – an opportunity that they received.” (MTD, p. 10). Furthermore, the “announcement of the giveaway on Instagram was accompanied by a list of ‘Frequently Asked Questions‘ (‘FAQ’) published on Draper James’ website….[T]he FAQ…explicitly disclosed that applicants would be ‘vetted and selected in a lottery.'” (MTD, pp. 11-12).

Draper James argued that plaintiffs’ attempt to turn the Instagram post into a “contract” “rests on a gross misstatement of the plain language of the promotion.” (MTD, p. 15).

“There is no support for Plaintiffs’ argument that the Instagram post guaranteed every entrant a free dress. The actual words in the Instagram post instructed individuals to ‘apply‘ through an entry form. It announced that ‘winners‘ would be notified on April 7. To reinforce these points, the Instagram post stated that the offer was available ‘while supplies last.’ Common sense and ordinary experience also confirm that the giveaway was of a limited quantity, and that not everyone would be receiving a free dress. Rather than indicating some sort of guarantee, the words and context made clear that signing up made one eligible to receive a dress (‘apply’), and that some entrants would be selected to receive one (‘winners’). Plaintiffs’ claim that there was ‘no indication this was some form of lottery’ is again contradicted by the terms of the promotion referring to winners, applicants, and limited supply. In addition, the FAQ Plaintiffs cite in their Complaint expressly told applicants that they would be ‘vetted and selected in a lottery.'”

(MTD, p. 16 (citation omitted)). Given the terms of the Instagram post and FAQs, it was implausible, therefore, for the plaintiffs to think that “there was no limitation on quantity whatsoever,” or that “a free dress would be delivered to them if they signed up for the promotion.” (MTD, p. 16). (“To survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint must contain sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.” Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009)).

As for the plaintiffs’ claim brought under the California Legal Remedies Act, Draper James argued that the claim failed because the plaintiffs were not consumers as they did not purchase or lease anything, the statute allows while-supplies-last promotions, and there was no reliance or misrepresentation – “it is not plausible that a significant portion of the public would believe that Draper James was offering an unlimited supply of free dresses through its promotion.” (MTD, pp. 19-20). Similarly, Draper James argued the claim brought under the California Business & Professions Code likewise failed because there was no fraudulent or unlawful conduct by Draper James or Reese Witherspoon. “[T]here was nothing fraudulent, misleading, or otherwise unlawful about [the promotion]—indeed Plaintiffs never allege that they actually thought that they would be guaranteed a free dress if they simply submitted an entry.” (MTD, p. 21). “[T]here is no fraud when a plaintiff reads a true statement and then assumes things other than what the statement actually says.” (Id. (citation omitted)).

Undeterred and apparently galvanized by Draper James’ motion to dismiss, the plaintiffs came out with a First Amended Complaint on July 17, 2020. While the plaintiffs make the same basic allegations and reassert the same claims alleged in the original complaint, they have added a sixth claim: violation of New York General Business Law § 349 alleging that defendants engaged in “an illegal sweepstakes promotion.” In addition, this First Amended Complaint attempts to address head-on some of the arguments raised by the defendants in their motion to dismiss, including providing a detailed explanation of how it is, in fact, plausible that the plaintiffs actually thought they would receive a free dress if they completed the entry form.

To explain how it was plausible the plaintiffs and all class members thought they would get a free dress, despite the terms of the Instagram post and FAQs, plaintiffs now allege that it was all about the timing:

“[T]he timing of this offer was critical, as it was being made at the same time other celebrities of Ms. Witherspoon’s renown were offering millions of dollars to COVID-19 victims with no strings attached. It is highly unlikely that national shows such as The Today Show and Good Morning America would have promoted ‘Reese Witherspoon’s clothing brand is giving away free dresses to teachers’…or ‘the Oscar-winning actress wants to show her gratitude during the coronavirus pandemic’ if they were aware Defendants were in fact only offering educators nationwide a sweepstakes chance to receive a dress that cost Defendants at most $43.15, while the average retail price for these dresses ranges from $88 to $295. Particularly considering Ms. Witherspoon’s popularity and the active promotion of this offer and the resulting exploitation of this response by bombarding consumers who responded with email offers to buy their goods and services, it was unreasonable to suggest that consumers would reasonably believe there were such strict limitations on this offer. Defendants apparently made a conscious decision to affirmatively conceal the material fact that this open offer, accepted by over 900,000 teachers nationwide [Draper James received 904,342 individual entries], was, according to Defendants, limited to 250 persons, despite having that information in their exclusive possession or having supposedly spoken on the issue in various public statements and advertisements. They could have easily stated during this promotional period ‘sweepstakes limited to 250 people,’ but did not.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 5).

To drive home their point that “timing was critical,” the plaintiffs take more than eight (8) pages of their amended complaint attempting to compare Draper James’ offer with what other fashion companies and celebrities were doing in response to COVID-19. The plaintiffs state:

“Beginning in late March 2020, public reports were circulating of the charitable giving offered by both fashion companies and media celebrities, both nation and worldwide…Defendants’ efforts were promoted alongside those of Oprah Winfrey, who donated $10 million for COVID-19 relief, and other celebrities of Ms. Witherspoon’s stature and fashion companies who made donations in the millions of dollars each.” The plaintiffs’ amended complaint includes a table of 46 fashion companies and a table of 37 celebrities setting forth what each was allegedly offering to support COVID-19 relief efforts. (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 38 and pp. 18-24).

The plaintiffs then say that:

“[t]his timing is important for several reasons, and explains the nature of the offer and the reasonable reaction of consumers that indicated they reasonably believed there were no unreasonable restrictions on Defendants’ offer. These announcements of charitable giving were being announced just days after California and other states were announcing statewide shutdown restrictions, in late March 2020. Defendants made this announcement in early April 2020, days after many of these other announcements. However, if Defendants had disclosed at that time what Ms. Witherspoon and her company were supposedly actually offering, which according to Defendants’ own information was between $6,537.50 and $10,787.50, as compared to what her peers in both the entertainment and fashion industry were offering, it would have been publicly revealed that there was no comparison. What Defendants were publicly passing off as a generous offer to teachers in need nationwide would have been recognized as likely only costing them less than $11,000, while more likely than not at the same time providing Defendants with personal information and marketing data valued in the hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars, which when combined with their promotional campaign could generate more in promotional sales than what they were offering to provide. There is no indication any of the other individuals and groups listed above took similar actions. What’s worse, as noted above even if only one-tenth of one percent of Class members accepted these promotional offers, Defendants would net more in sales and profits from these new consumers than the total cost of their supposedly generous proposal — all at the expense of educators who are on the front line of this COVID-19 crisis.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 39).

According to the plaintiffs, “[t]his public promotion and support, and the resulting backlash when the supposed material facts were later revealed, shows how this undisclosed limitation would be material to both Plaintiffs, Class Members, and the public, as reasonable consumers under the circumstances would not have thought this was a sweepstakes or lottery subject to unreasonable restrictions later imposed by Defendants.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 41). Indeed, again according the plaintiffs, “Ms. Witherspoon and Draper James are sophisticated e-commerce participants who likely know what facts are material to consumers and either did or reasonably should have gauged the likely response from making such an offer to enter into such agreements. While Defendants could afford to honor such requests, as Ms. Witherspoon’s net worth is estimated at approximately $240 million as of 2019 according to Forbes, they decided not to do so.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 57).

As to the defendants’ argument that the phrase “while supplies last” put the plaintiffs on notice that not every registrant would be getting a free dress, the plaintiffs responded with the allegations that:

“[f]irst … such a disclosure was not clear and conspicuous in its context, and certainly nowhere disclosed Defendants had unilaterally limited its offer to 250 individuals. Second, the use of such phrase as a matter of marketing practice merely reinforces the conclusion this was an advertising scheme or plan in connection with the promotion, advertising or sale of consumer goods. Programs in which there are offers that contain phrases that indicate there is a scarcity in supply, without stating what that scarcity actually is, have been shown to actually stimulate interest and invitations to act rather than provide the alleged disclosure claimed by Defendants. This is particularly the case when, as here, there was an urgency created by making the offer available only for a few days, starting on a Thursday and ending on a Sunday.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 35 (citation omitted)).

Furthermore, in the new claim now being made by the plaintiffs, they allege that “if Defendants are to be believed that this was merely some form of sweepstakes or lottery, they engaged in illegal conduct and did not comply with the laws that apply to such sweepstakes or lotteries — laws that they are fully aware of. Defendants engaged in unlawful business practices and specifically violated both California law and New York law (where Draper James claims to be based), and operated this scheme to enrich themselves, using the interstate mails and wires to do so.” First Amended Complaint, ¶ 9 (emphasis added). “Defendants have asserted that the use of the terms ‘while supplies last’ and ‘winners’ placed Plaintiffs and Class members on notice that not every person who submitted an entry would win a dress, and that they would be randomly selected from the registrants. In making this claim, Defendants have asserted they were offering persons the ability to participate in a ‘sweepstakes’ or lottery for a free dress. A ‘sweepstakes’ is defined in Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code Section 17539.1 as ‘an activity or event for the distribution, donation, or sale of anything of value by lot, chance, or random selection,'” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 58) and California law has specific requirements for these to be permitted, including the creation of Official Rules, which the plaintiffs’ allege Draper James failed to create. (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 59).

Plaintiffs also now allege that Draper James and Reese Witherspoon have per se violated New York General Business Law by engaging in illegal conduct. Draper James’ “sweepstakes” violates New York General Business Law 369-e (which plaintiffs reprint almost in full in the amended complaint) including the provisions that make it a Class B Misdemeanor – see pages 34-35 of the First Amended Complaint), because, the plaintiffs allege, among other things “there is no indication that Defendants registered their sweepstakes with the New York Secretary of State; made the required filings with the Secretary of State and provided the required filing fee; posted the required bonds with the Secretary of State or set up the required trust accounts; posted the information required in subdivision (2) in retail stores or disclosed that information with any advertising disclosing the promotional offer; filed the list of winners and the other information required by law with the Secretary of State and made it publicly available upon request; made any of the undisclosed ‘rules’ available, or otherwise complied with this law in any way.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 62).

The plaintiffs further allege that:

“[t]his was not some technical or inadvertent oversight, since sweepstakes are a way of life for Draper James. For example, in August 2019, Draper James operated a sweepstakes giving away a total of two swimsuits to exactly one entrant. As here, the promotion was only open for a few days. As here, Draper James claimed the ‘winners’ would be notified shortly after the offer ended. And as here, registrants received unsolicited advertisements when the registrants provided their contact data as part of this sweepstakes (much less personal information than requested here), but enough to added [sic] to their marketing customer lists. See https://draperjames.com/pages/sweepstakes. But unlike here, Draper James attempted to comply with the above referenced sweepstakes laws. Here they made no effort to do so. Thus, Defendants were fully aware how to disclose they were running a sweepstakes operation at the time of this offer, and had already used a similar promotion as a marketing scheme and were set up to do so. Yet they failed to do so here, in violation of such laws.” (First Amended Complaint, ¶ 64).

I expect that Draper James and Reese Witherspoon will file another motion to dismiss (as the one they had filed is now moot due to the filing of the amended complaint), but it remains to be seen whether the plaintiffs did enough to plead a claim that is plausible on its face in light of the terms of the Instagram post on which they must rely. Is it enough to say that what the plaintiffs thought about the promotion, despite its terms, was reasonable in light of (i) the particular timing, (ii) the existence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iii) a comparison of Draper James, a boutique fashion line that by plaintiffs’ admission sold only 150,000 dresses in 2019, to other fashion labels and media celebrities, especially where there is no allegation that the plaintiffs or all class members even knew what these other groups were doing at the time, and even if they did, could they or should they have relied on that?

***Reese Witherspoon and Draper James did, indeed, file another motion to dismiss in response to the plaintiffs’ amended complaint. While very similar to the original motion to dismiss, they do include the following additional information to demonstrate the implausibility of the plaintiffs’ claims: on April 2, 2020, it already was widely reported that the number of dresses to be given away was 250.